Torque and BHP explained

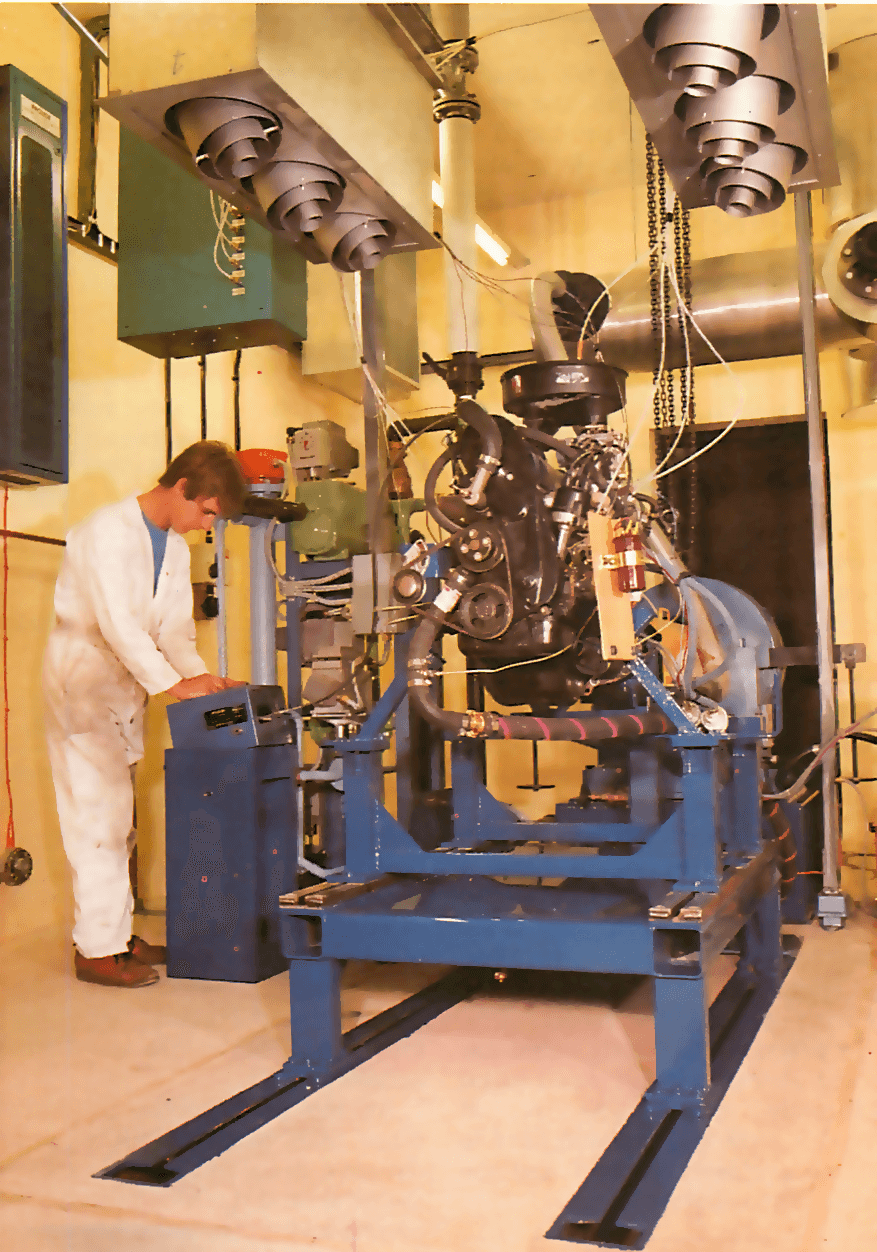

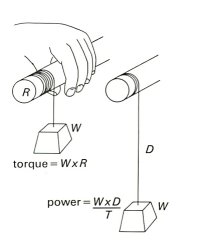

An engine’s power is measured by running the engine against a load on a dynamometer. The braking effort needed to hold the engine at a steady speed on full throttle gives the torque. The power can then be calculated by multiplying the torque by the engine speed.

An engine which produces a lot of torque over a wide range of engine speeds

will be relaxing to drive because fewer gearchanges are needed: the engine’s

torque is often sufficient to accelerate the car without changing down. At

cruising speeds a lorquey’ engine will not need to be turning over very quickly

because it can pull at high gearing, which makes for good

economy.

Engines that produce a lot of power for their size do not usually produce so

much torque, and what torque there is is often produced at higher engine

speeds. It is also likely that the engine will be producing usable torque and

power over a smaller range of engine speeds; this narrow ‘power band‘ makes the

engine less suitable than a torquey or ‘lazy’ engine for jobs such as towing,

and the car will be less relaxing to drive.

Typical figures

A fairly typical small family car engine puts out, say, 60bhp (brake horse

power) at 5000rpm. The same engine can be tuned or modified so that it gives

80bhp at 6000rpm. But although the power is greater, the peak torque can

actually be less, as well as occurring at a higher engine speed. There will be

less torque at low and medium engine speeds.

In other words, though a car with the tuned engine would have a higher

maximum speed, it would only accelerate better as long as the gearbox was used

to the full to keep the engine speed up, assuming the gearing remained the

same.

In practice, the highly tuned car would almost certainly need to be

differently geared to remain drivable – the gears would have to be more closely

spaced and the overall ratio slightly lower.

Measuring power

The usual engine test procedure is to run the unit on a ‘brake’ or

dynamometer which measures torque over a large range of speeds by seeing how

much braking effort is needed to keep the engine at a steady speed on full

throttle.

The torque times the engine speed then gives the power output, called brake

horse power (bhp). Power measured like this, with the engine on a test bed, is

expressed as a power output at the flywheel.

It is possible to run the car on a `rolling road’ dynamometer to measure the

power output at the driving wheels instead. This is less than the power at the

flywheel because of frictional losses in the car’s transmission system, but it

gives a more realistic idea of how the car will perform as it shows how much

power reaches the road.

Torque/bhp balance

Every engine designer has to bear in mind the balance between power and

torque. He might even move the balance a little away from power and towards

torque if enough drivers understood the importance of torque and the

generalization that power versus aerodynamic drag determines maximum speed, but

torque versus weight determines acceleration.

As the car speeds up, forces other than weight, such as aerodynamic drag,

rolling resistance of the tyres, and the friction within the engine and

transmission, act on it to try to resist this acceleration. At a certain speed,

these drag forces equal the car’s driving force, or torque, and there is no

excess power left for further acceleration.

Gearing

Changes in gearing are important when looking at power and torque,

because the gears act as torque multipliers.

If first gear has a ratio of 3:1, it multiplies the engine’s torque

output by three when passing it on to the final drive. Similarly, the final

drive ratio, typically around 3.5:1, multiplies the torque from the gearbox

by that much again.

In first gear, therefore, the torque delivered to the driving wheels can

be around ten times greater than the engine’s torque output, while speed of

rotation will have reduced by a similar factor. This gearing down is

necessary because one of a piston engine’s biggest drawbacks is its poor

torque at low speed.

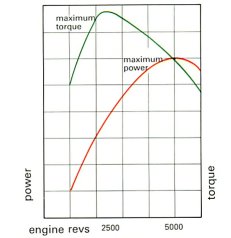

Torque and brake horsepower curves

The amount of power an engine develops can be measured on a dynamometer

and the results plotted on a graph. Shown here are typical curves for an

engine in what an engine tuner would call ‘road tune’ and ‘fast road tune’

states.

Road tune (near right) is the compromise between power/torque and fuel

economy that a car manufacturer builds into a typical car engine when

designing it.

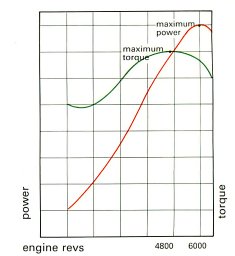

A fast road tune engine (far right) sacrifices some fuel economy for

increased power. The amount of torque is overall slightly less, and the

maximum torque occurs at higher revs. Such an engine develops more top-end

power which would give a higher top speed, but its decreased overall torque

requires higher revs for the same power output and more gearchanging — a

less ‘lazy’ drive.

Above fast road, it is possible to tune the engine to increasingly

higher levels known as ‘road/rally’, ‘rally’ and ‘race’. But the greater

power output is paid for, apart from decreasing fuel economy, by the torque

band moving to higher revs and becoming narrower—the car increasingly loses

its flexibility.